Publish Date: Kas 21, 2018

Brands are losing out on £774bn by failing to bridge the ‘self-esteem gap’

Brands are missing out on billions of pounds by failing to take a gender-balanced approach to marketing that supports, rather than undermines, the self-esteem of female consumers. This is a serious oversight given that 80% of household purchase decisions are made by women.

New research released today (21 November) by Kantar shows that brands which promote gender-balanced marketing are worth £774bn more than their rivals. The brand value of brands skewed towards men is £3.1bn, compared to a value of £4.1bn for brands that are either ‘balanced’ or skewed towards women.

Furthermore, these female-skewed brands are 4% healthier than male-skewed brands and 6% healthier than strongly male-focused brands.

Despite the fact brands are seeking to improve the representation of women through initiatives such as the Unstereotype Alliance, two-thirds of women responding to Kantar’s What Women Want? study say they skip adverts they feel are negatively stereotyping women, while a further 85% describe film and advertising as doing a poor job of depicting real women.

While 55% of the 2,000 male and 2,000 female respondents agree that movements like #MeToo have made gender equality a more prominent issue, just 37% of women and 43% of men think gender equality has improved compared to 12 months ago.

The What Women Want? study also suggests that brands are failing to appreciate the importance self-esteem plays in female empowerment and how this affects how women feel about brands.

A UK-based sample of 2,000 women were asked to rate 40 mass market brands through the lens of self-esteem across eight different categories from travel, banking, fashion and FMCG to automotive, beauty, supermarket retail and social media. The answers were then split on the basis of whether the women self-identify as having low or high self-esteem.

Brands seen as making a positive contribution to the respondent’s self-esteem had a score closer to 100, while those seen as making a negative contribution were rated closer to zero. The gap in the perceptions was calculated by subtracting the score of women with low self-esteem from the women who self-identify as having high self-esteem.

The Kantar analysis shows that brands typically contribute more to those with high self-esteem than low self-esteem, meaning it is easier for brands to “endorse” self-esteem than it is to create it.

The brand winners and losers

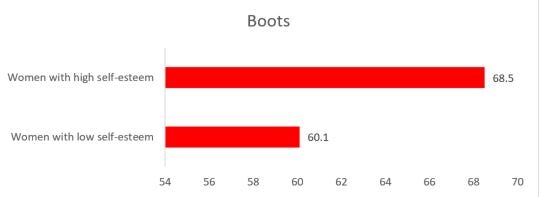

Boots scores highly as an inclusive, accessible brand that appeals to shoppers by showing a varied portrayal of women in its advertising. It was the most liked brand by both the women with low self-esteem (60.1 out of 100) and high self-esteem (68.5), with a gap between the two groups of 8.4 points.

Performing really strongly in the challenging financial services category is Nationwide, which appeals to both women identifying with low (51.1) and high self-esteem (52.9), producing a gap of just 1.8. The results speak to the effectiveness of the building society’s positioning around mutuality and being a inclusive, partnership-led brand.

Questions hang over the inclusivity of John Lewis, however, which emerged as the brand with the biggest gap between women with low self-esteem (46.3) and high self-esteem (63) of 16.6 points.

Amy Cashman, managing director UK of Kantar TNS, explains that John Lewis has historically been seen as quite an upmarket brand, which can be a bit off-putting. The business is also seen as being south-centric having only recently increased its footprint across the country.

“While it has this thing about never knowingly being undersold, John Lewis is often seen in the tracking data we have as a brand that’s more expensive. To us it doesn’t necessarily feel like it is a brand for everybody. A brand for people of higher social grades is how it’s normally seen when you ask people in the wider population,” Cashman explains.

[Marketers’] job is to make sure we’re accentuating the good and making sure that people have that accessibility and can find other views, outlooks and challenges so they can help process things.

Philippa Snare, Facebook

Nike is the brand with the second biggest gap between women with low self-esteem (46.8) and high self-esteem (62.7), creating a gap of 15.8. Kantar noted that the focus of its advertising is more on professional athletes like Serena Williams than real women, which can exclude women who are new to exercise or are not aspiring to this kind of athleticism.

Online investment management startup Nutmeg was singled out as a brand that is relatively balanced between women with low and high self-esteem. Women who describe themselves as having low self-esteem (52) actually prefer the brand compared to women with high self-esteem (49.8), creating a gap of -2.2.

Kantar acknowledged that the brand does a great job of bringing people into a complicated category that traditionally uses quite difficult language, which is tricky to understand.

The only other brand that appeals more to women with lower self-esteem is Marks & Spencer (50 vs 46.7 points). Cashman explains that this is not a problem for M&S, but it could make the company think again about its targeting.

“In some ways it’s nice that a mass market brand like Marks & Spencer doesn’t have a difference on this measure, that everyone feels included, but perhaps it points to the wider challenge they have around targeting,” she states.

“In general if you’re a mass market brand you don’t want to be isolating large groups of the population. They need to think about their wider targeting strategy and how much they can achieve by being totally mass market.”

The gap is more of a problem for fashion retailer Zara. The research shows that the Spanish fashion giant is failing to appeal to women with low self-esteem (47.6), despite being a hit with women with higher self-esteem (61.3). The gap of 13.6 is almost double that of fast fashion rival Asos at 7.8 points, which according to Cashman is managing to create broader appeal thanks to the breadth of it ranges and commitment to using models in a variety of sizes.

Changing the conversation

The research found that self-esteem is highly nuanced, very personal and attached to five contributing factors – financial autonomy, freedom of thought and expression, sexual and body autonomy, accessibility/visibility and social connections/networks.

Crucially women’s self-esteem was found to be considerably lower than men’s. Just 20% of women surveyed said they would describe themselves as having above average self-esteem, compared to 38% of men, whereas double the amount of women (30% vs 15%) would describe themselves as having below average self-esteem.

Millennial women, aged between 18 and 34, are even more likely to report themselves as having below average self-esteem (35%) compared to millennial men (15%).

Cashman argues that there are still intrinsic beliefs about what women are, what women do, what they shouldn’t do, which is holding women back from improving their self-esteem.

She argues that while 20 years ago there would probably have been a difference between the self-esteem of men and women, the gap now between millennials is being perpetuated by the pressures of social media.

“Let’s be clear, social media can be really brilliant in this area because it gives people a connection and a network that they otherwise wouldn’t know and it helps them feel supported,” Cashman explains.

“There’s both sides to the social media debate on this one. But there’s no question it does create some pressures and images that perhaps weren’t there 20 years ago.”

Facebook global head of business marketing and member of the What Women Want? steering committee, Philippa Snare, does not believe that the lack of self-esteem among millennial women is all down to social media.

Speaking to Marketing Week, Snare argued that social media offers up opportunities for people to connect and find support, with the communities that tackle real issues head on actually thriving.

“With everything in life there’s goods and bads, and our job is to make sure we’re accentuating the good and making sure that people have that accessibility and can find other views, outlooks and challenges so they can help process things,” she explains.

There’s both sides to the social media debate on this one. But there’s no question it does create some pressures and images that perhaps weren’t there 20 years ago.

Amy Cashman, Kantar

Snare believes brands have a responsibility to use their platform to help those communities gain a bigger voice and argues that they should be braver at owning some of the issues that really matter to consumers.

“As a result of doing that they will naturally form relationships with a wider part of society with different decision makers, with different people who have spending power and they will be rewarded because they are reflecting what people are already thinking, doing and saying,” she adds.

WPP country manager Karen Blackett OBE, a fellow member of the steering committee, adds that while it is brilliant for society that brands are trying to be more representative, the research shows there is a long way to go.

“It’s about brands recognising how the UK has changed and recognising there are more opportunities to be inclusive if they want to deliver profit,” she states.

“The world around us has changed, but we’re not changing quickly enough to reflect that change in our organisations.”

Cashman agrees that if change is to accelerate brands must listen to consumers, who are broadly asking for diversity and to be represented in different ways. She advises brands to assess whether their narrative and communications are one dimensional, whether they exclude anybody or alienate anyone, and then use the language of consumers to change the conversation.